Central African Republic

Religious violence between Christians and Muslim is worsening in the Central African Republic. NGOs, aid workers, policymakers (such as French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius) and UN representatives have issue warning of the violence spiralling into genocide. Amnesty International said war crimes and possible crimes against humanity may have been committed – people have been killed, raped and kidnapped. A clear sign that the conflict is escalating is the increasing number of child soldiers, now estimated at 6,000.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon first urged the Security Council to authorise the deployment of 6,000 blue berets but now says that another 3,000 should be on standby in case things get worse. “This cycle, if not addressed now, threatens to degenerate into a country-wide religious and ethnic divide, with the potential to spiral into an uncontrollable situation, including atrocity crimes, with serious national and regional implications,” he said. According to the UN’s Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng, Christians and Muslim will end up killing each other if nothing is done now. He did not exclude the possibility of genocide occurring. In an extensive article titled “Unspeakable horrors in a country on the verge of genocide” David Smith asks “What needs to happen before the world intervenes?” This question is certainly legitimate once again.

The problem is that UN peacekeeping forces are slow to deploy. I have also seen very little political will, at least in the West, to prevent an escalation of the conflict in a decisive manner. The only country that has stepped forward is France, who backed a UN resolution in October. The Central African Republic may be a big country but in terms of international attention, it gets very little from world leaders, policymakers or the general public.

Evan P. Cinq-Mars, who works at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, wrote a good op-ed in The Ottawa Citizen in which he argues that while warnings have been issued the situation resonates with what happened in Rwanda and Darfur. Words and lots of tip toeing but no action. There is no genocide yet but if nothing is done, that we may be heading in that direction.

Thierry Vircoulon, Africa expert at the International Crisis Group, wrote this piece in which he underlines (as many think tanks and activists often do) that “prevention of a crisis is much better than a cure — and much cheaper.” While CAR has a long history of conflict, the current escalation of violence could have been avoided if regional bodies such as ECCAS and the AU had agreed on a political solution to the crisis, put more pressure on the transitional “government” to protect civilians, and if the AU’s peacekeeping force had more resources and support. Now refugees are fleeing to neighbouring countries and there is a real risk of spill-over. CAR could also become a safe haven for terrorists groups such as Boko Haram. Consequently, it would be wise for the international community to act.

Myanmar: no citizenship for the Rohingya

On Tuesday, the UN asked the government of Myanmar to grant citizenship to the Rohingya, a stateless minority group that I have previously written about. A government spokesperson replied that “”We cannot give citizenship rights to those who are not in accord with the law, whatever the pressure. That is our sovereign right.”

Considered as illegal immigrants and “Bengalis” (a pejorative term) by Burmese authorities as well as the Burmese citizen, the Rohingya have long been persecuted and violence, including pogrom-like attacks, against them has increased since Myanmar embarked on a reform drive.

The authorities’ refusal to recognize the Rohingya is a clear sign that they are being discriminated against.

Nyan Win, a spokesman for the National League for Democracy party of Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, agreed with the government’s position and added that “the Rohingya do not exist under Myanmar’s law.”

Lord’s Resistance Army: Little hope to catch Kony despite rumors of talks

Last week a spokesperson for the President of the Central African Republic, Michael Djotodia, claimed that the president is currently in talks with world-known LRA rebel leader Joseph Kony, and that the latter may surrender. President Djotodia reportedly said: “Joseph Kony wants to come out of the bush. We are negotiating with him.”

What to make of these claims and the possibility of surrender? Very little. While the LRA has been weakened in recent years and probably feels under pressure, many remain sceptical, including Ugandans. We’ve heard to story before. The US State Department, which has backed efforts to hunt down the LRA, does not give much weigh to the claims either, arguing that Kony and his top men use this tactic “to rest, regroup, and rearm (…).” Similarly the AU’s special envoy on the LRA said that Kony may be trying “his time-tested tricks of buying time by duping the CAR authorities into negotiations”.

We also have to consider where this is coming from. Michel Djotodia became president after ousting President Bozizé with the help Seleka, a rebel coalition that is committing widespread abuses in CAR. By now the country has pretty much become a “failed state.”

Nonetheless, Joseph Kony has been weakened. In the end perhaps, continued military pressure may “bring him out of the bush” but since we are aware of his bluffing tactics, that kind of pressure should continue in order to prevent his men from reorganizing.

Conflict Diamonds and the efficiency of the Kimberley Process

A new map of the eastern DRC reveals that artisanal mine sites controlled by armed groups (200) or by the Congolese army (265). It shows the location of 800 mining site, cases of illegal taxation by armed groups or the army Researchers at the International Peace Information Service (IPIS) found that gold is the number one conflict mineral in the region. The rise as the first conflict mineral is both the result of the high value of gold and stricter anti-conflict minerals legislation, gold being easier to smuggle than tin, tungsten and tantalum.

Although there have been significant efforts to guarantee conflict-free mineral, there are loopholes in the supply chain, a clear lack of monitoring and due diligence. Governments in the region are clearly not imposing sanctions on those who buy minerals from armed groups.

There has been quite a lot of debate on the need to reform the Kimberley Process (KPSC), a mineral certification process founded in 2003. Delegates from 81 KPCS member countries called for stricter sanctions. One of the biggest criticisms made by NGOs is the weak definition of conflict diamonds. Described as “rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance conflict aimed at undermining legitimate governments”, they do not include state entities (ex: Zimbabwe in 2008). Times Live looks at the double-standards of the diamond industry.

The Justice vs. Peace Conundrum

“What place should the international community give to justice and accountability in its response to conflicts involving mass atrocities? Under what circumstances does the effort to pursue justice help or alternatively complicate the effort to bring atrocities to an end? Is it better to set a benchmark for justice by referring active conflicts to the International Criminal Court, or should efforts to seek justice be deferred until a peace deal is being discussed?” These are the questions raised by the European Council on Foreign Relations project on International Justice and mass atrocities. The goal? Examine the effects of international justice mechanisms on conflict resolution, the relationship between bringing violence to an end and holding perpetrators of mass atrocity crimes accountable: “How far are those two objectives mutually reinforcing, and how far are they in tension?” The debate over “peace vs. justice” is not new but the project takes a refreshing look at the debate thanks to the variety of case studies it examines as well as the impressive quality of scholars/experts Anthony Dworkin and the ECFR managed to gather. The ECFR commissioned 12 case studies in order to look at the variety of approaches and their consequences: Afghanistan, Bosnia, the DRC, Israel and Palestine, Kosovo, Liberia Libya, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Syria, Uganda and Yemen. The case studies are short and concise.

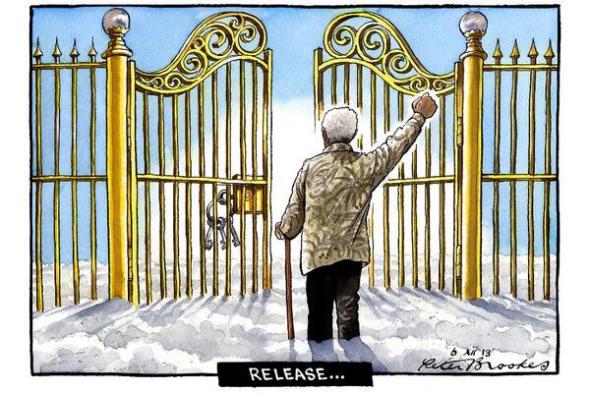

On the same, subject Al Jazeera presenter Mike Hanna sat down with the former President of South Africa to discuss the problem of peace and conflict, especially at time when many African leaders are rising against the ICC. Should justice trump peace?

DRC: one down but many others left

I have seen some optimism in Congolese and international media about the situation in the DRC. However, while the M23 may been militarily defeated there are other armed groups the DRC must still deal with. As this article by Ida Sawyer rightly argues, “it is by no means the end of Congo’s brutal story.” The M23 leaders and many of the rebels have found refuge in Uganda and Rwanda, who refuse to hand them over. No political solution has been found either so the cycle of conflict may continue. Foreign (the FDLR for example) and Congolese militia groups (self-defense groups such as the Mai Mai Sheka and Raia Mutomboki who are fighting the FDLR) are still very much present, especially in the eastern DRC, and continue to commit abuses against civilians. Similarly, in “An elusive peace” on The Economist’s Baobab blogger emphasizes the importance of a political deal with the M23 – the absence of a deal, considering the presence of M23 rebels in Rwanda and Uganda, is an “accident waiting to happen.” But the blogger also emphasizes on the need to track down the FDLR since Rwanda is unlikely to stop interfering in the DRC as long as these rebels are present in the Congo.

While the government and the UN may have won the fight against the M23, as Sawyer concludes “the road toward peace will remain as long as ever.” And this is without taking into consideration all other challenges, such as good governance and corruption, justice, reconciliation, and security sector reform. Amani Itakuya – Peace will come has published a list of articles written by journalists, academics, activists, and practitioners on the challenges and opportunities of peace building in the Congo and the Great Lakes region. This collection of articles allows us to get different views and arguments on a variety of subject linked to challenges in the region: conflict minerals, justice, the FDLR and the M23, the role of regional tensions and international intervention, security sector reform, ethnic conflict, and reconciliation.

Technology: Twiplomacy study

Since the rise of social media, world leaders, policymakers, and international and regional organizations have embraced these new digital media to communicate and increase their impact. A new Burson-Marsteller Twiplomacy study looks at the way international organizations use Twitter and what we can learn from it. While some people may think of Twitter as something obsolete, they must realize that it has opened new communication channels. A lot of diplomacy occurs in the Twittersphere. These days important news, events or statements are tweeted before they appear on websites and certainly in traditional media. Statements, and judgments are made, debates and protests occur, and individual leaders also use Twitter to chat with their followers, thereby opening new communication channels. Imagine, combined, all organizations studied here have sent 770,547 tweets!

The Twiplomacy study focuses on 223 accounts from 101 international organizations, 51 personal accounts of these organizations’ leaders and 75 accounts in other languages. The research analyses each organization’s Twitter profiles and their recent tweet history based on 50 variables, including followers, retweets, replies and hashtags.

UNICEF is the most followed international organization. To measure an organization’s effectiveness, the research took into account the number of retweets (RT). The European Organization for Nuclear (CERN) comes first, followed by UNICEF and the UN. To measure popularity, the study also looked at the number of times an account appears on Twitter lists. Here the UN comes first, followed by CERN, UNICEF, Greenpeace and WHO. You can also have a look at the most followed and the most conversational leaders